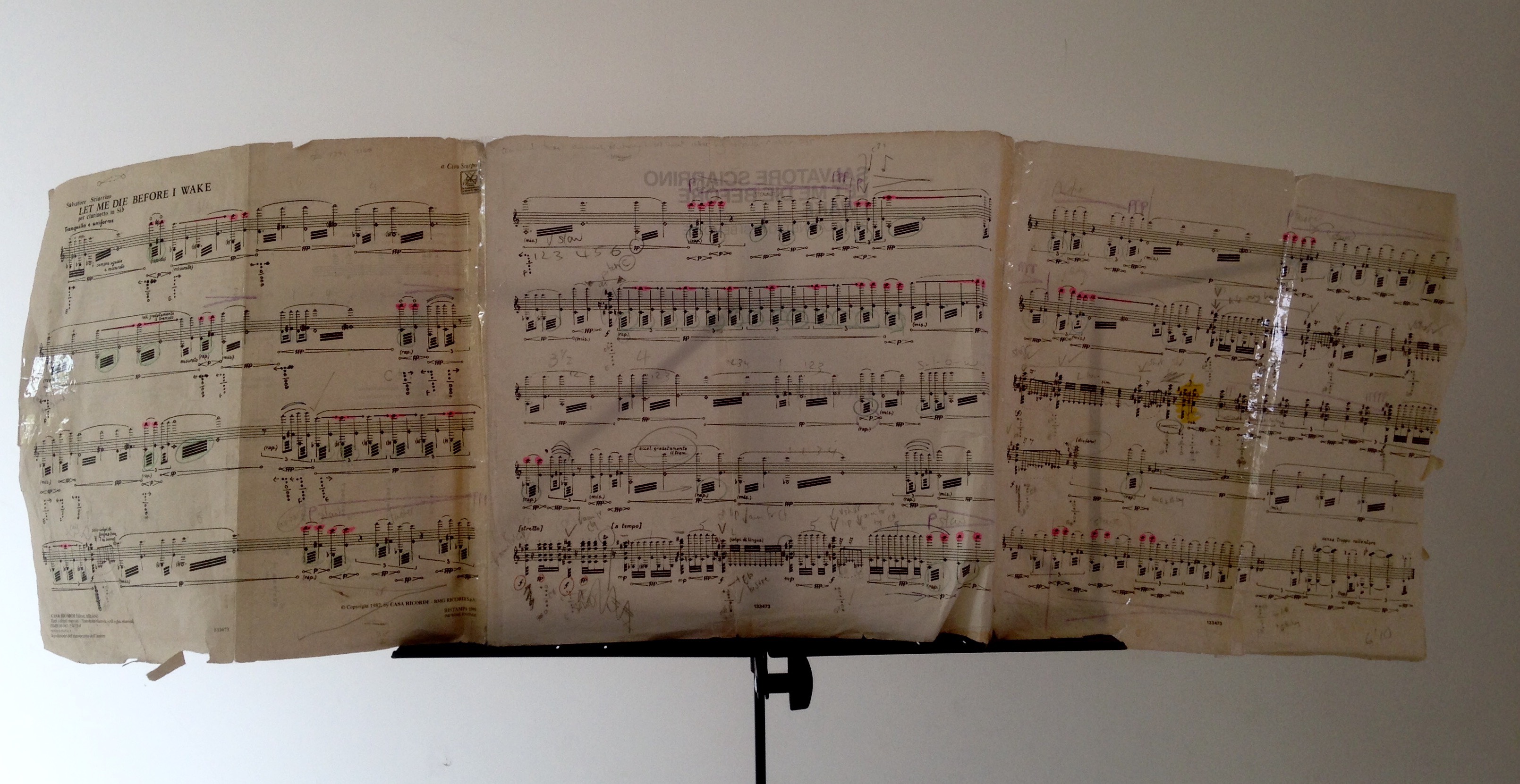

This is what a much-loved, much-played musical score looks like. This is a piece of music that has travelled in the zip-up compartment of an instrument case on trains, in cars, planes, has visited concert halls, rehearsal rooms, coffee shops. It is dog-eared and tattered. The paper is yellow, thin, softened with repeated turning and held together with tape where the folds have weakened and torn. It has scribbled annotations and someone’s phone number on the back.

I’m performing this old friend (Salvatore Sciarrino’s Let Me Die Before I Wake) tomorrow. As I retrieved my fragile score from the shelf and carefully balanced it on the music stand I realised how little I needed its signs and symbols, yet how much I enjoyed being in the company of my ageing artefact.

I’ve always loved musical scores. Aged 18, I bought Birtwistle’s Linoi for clarinet and piano. It was such a beautiful object that I stuck it on the wall of my student room, quite content to gaze on it like I might revere the Wren drawings for St Paul’s Cathedral – a blueprint for a vision, a design for something extraordinary and not yet realised. Like architects’ plans, musical scores have an authority and an aura of their own, independent of what they may become. They have a talismanic quality – a mix of sentiment and magic.

We musicians are fortunate to have our own language in which to express our ideas. ‘The poet envies the musician constantly’ said Hermann Hesse: ‘How handicapped [the poet] is in having no individual instrument for his art; no dwelling of his own, no private garden, no attic window through which to look at the moon’. And what a language this is; resourceful, streamlined, consistent. How little visual wastage there is in a musical score (think of the cluttered, chaotic look of a toy catalogue…). How elegant a method this is for gauging interest, drawing us in like a peacock’s tail. A quick glance at a score enables us to take in an astonishing amount of symbolic information as to what ‘sort’ of a piece it is and whether we might like it.

This Sciarrino score has been with me for nearly twenty years. Now, in 2017, I love the feel, the patina, the delicacy of this waif-like triptych on the stand. I love the softness of the manuscript; it could wrap itself around me like an old, thin t-shirt. If Sciarrino’s notation was the map, then the marks, the folds, the tears and the fixes have been my journey through it, my personal footprints that have worn away a path over many years of performance. I like to think that my performances have also matured, from the crisp, breezy exploration of a new adventure to a more gentle and deeper appreciation of this musical hinterland. I’m more ready to notice other things around me and allow them to erode my more youthful ideas about this music. A performance is never really complete, never fixed, never ended. I’m proud of my shabby score because this is what true affinity with a piece of music feels like and looks like. Its my personal affinity, but what a rewarding experience it is for a performer to feel they have truly mapped the landscape of a once-unfamiliar place.